* Every November 11, Remembrance

Day, Canada

The Royal Canadian Air Force

(RCAF) operated extensively over Europe during World War Two, most notably in the night-time

strategic bombing campaign over Germany Canada Britain Canada

The great victory over Germany

At first, Canada Europe

would change that.

The German blitzkrieg through

Poland Denmark Norway Netherlands Belgium Luxembourg France Europe

found itself trapped against the Channel coast in Dunkirk France Britain

The 1st Canadian Division,

which had recently arrived in England British Isles ! The sudden and devastating German attack on the west

had taken everybody by surprise, and with the defense of all of England Ottawa

.

Under heavy aerial bombardment, the British army evacuates from Dunkirk, leaving all their weapons and equipment and behind.

Because England is an island, the German air force, the Luftwaffe, was forced to knock out the British Royal Air Force before an amphibious invasion could be launched. The Germans had at their disposal over 2,000 warplanes of all types, while the RAF could summon 600 fighters. All summer of 1940 the skies over England were filled with battling airplanes as the Nazi war machine threatened to ground the RAF into dust and open the door for invasion. The British, however, hung on and fought back tenaciously, helped out by the new radar technology and an intricate ground-control system, staffed almost completely by women, that allowed operators to direct fighter squadrons to intercept German formations as they came over the Channel.

As the Battle of Britain dragged on over the summer and into the fall, the situation became desperate for the RAF. The pure weight of numbers favoring the Germans was beginning to tell, but then, one night, a German bomber crew got lost over England and decided to ditch their bombs and return home. They were over central London, which had been strictly off limits to bombing under Hitler’s express orders. The bombs hit a movie theatre and killed 40 people. The British, incenses, responded by bombing Berlin the following night. Although the British bombs failed to hit anything, Hitler was enraged (he had promised that Berlin would never be bombed), and he turned the full fury of the Luftwaffe onto London. The Blitz had begun, and with it, the devastating air war that would come to dominate Europe for the next 5 years.

The Blitz, as the bombing of London is known, lasted from September 1940 until spring 1941 and killed 40,000+ British civilians.

Londoners adopted an attitude of “Business as usual” and continued their daily lives in spite of the death and devastation around them. It was a show of defiance to the Germans who were inflicting such misery on them.

At the highest levels of the War Ministry, organizers were piecing together a plan that would allow England to hit back. The British army was in no shape to take on the German Wermacht, and Hitler had all the resources of the continent at his disposal. Britain turned to her Commonwealth for help. Canada was chosen as the main site for training aircrew and manufacturing warplanes. Canada was out of range of German bombers and the RCMP had locked the country down to German spies. The “Comonwealth Air Training Plan” was born, to which Canadian Prime-Minister MacKenzie-King quickly signed on. Over the next five years, 231 airbases would be built in Canada, and 110,000 men and women from Britain, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada would be inducted and trained in everything from radar operations to flying high-speed fighter planes.

In 1941 the first Canadian bomber squadrons were arriving in England to take part in the planned bombing offensive against Germany. Early raids were woefully unsuccessful. German air defences were strong and the Commonwealth air crews who participated suffered apalling losses. The British high command switched to night bombing for better safety. The technology at the time, however, rendered night-time bombing highly useless. It is estimated that only 15% of the bombs ever came within 5 miles of their target! The Whitley and Halifax bombers in use at the time had little armor and limited range. German flak (anti-aircraft guns) defences were growing stronger and the military planners were starting to realize that hitting small targets, such as a factory or a rail junction, at night was impossible.

In June of that year Germany invaded the Soviet Union in what would become the most destructive war in all of human history. Every Luftwaffe plane was needed on the eastern front and the Blitz on England came to an end as German resources were transferred east. The Russians managed to stop the German onslaught at the gates of Moscow, in Hitler’s first defeat. At the same time as the Russians were fighting for their lives outside their capital, Japanese naval forces bombed the American fleet at Pearl Harbor, and the war became global.

Canada switched to Total War production in 1940. As the men went to war, women entered the factories and began producing the material needed to save the world from fascism.

The Commonwealth Air Training Plan would see more than 110,000 young aircrew from around the world pass through Canada.

40,000 young women from across the Commonwealth also passed through Canada, learning essential skills required to keep the bombers in the air.

RCAF recruiting poster. People who applied and then failed the aptitude tests wer automatically sent to the infantry, where survival was less likely.

With the entry of the US and USSR into the war, and the defeat of Germany at Moscow, victory seemed certain. Allied (as the US and British Commonwealth was now called) planners put together a master strategy for the eventual defeat of Germany. While the Russians battled the Germany army in the east, the Allies would conduct an around-the-clock bombing campaign designed to destroy Germany’s industry. The Americans, with their advanced and powerful bomber fleets, would pound Germany factories by day, while the British and Commonwealth, with their 2 years of night flying experience, would level entire German cities by night. The idea behind the deliberate targetting of German cities was that without a workforce or any infrastructure, Germany couldn’t produce the tanks, bullets, oil and food necessary to wage modern war.

The first big raid of the war was the night of 28 March, 1942. The German port city of Lubeck received a firebombing by 234 heavy bombers. The city was gutted and the surviving population fled in terror to the countryside. Then, a month later, Bomber Command managed to assemble 1,000 British, Canadian and ANZAC bombers together for a terrible night raid on Cologne. The first of the ‘thousand bomber raids’ had begun.

Cologne suffered extensive damage. The fires that were started could be seen 600 miles away in France. 1,000 people were killed and another 45,000 were forced to evacuate. 35 factories were completely destroyed. The cost was heavy for Bomber Command, however. 40 bombers, including 12 Canadian aircrew, were lost to flak.

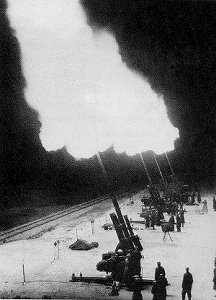

Flak was the main defensive measure German cities were able to adopt. Most of the bigger cities were ringed by batteries of 88mm heavy anti-aircraft guns and smaller 40mm automatic guns. When a raid was inbound they would fill the sky with a deadly wall of steel that the bombers were forced to fly through. Radar-guided searchlights scanned the night sky, and when one beam caught an airplane, all the others would flick over to illuminate it in a cone of light. Every gun below could then concentrate its fire on that one unfortunate bomber.

At this stage in the war night fighters were not that advanced. Pilots who had proven they had excellent night vision were thrown into the sky to try and meet the incoming Allied bombers, but it was difficult to see anything at best. Sometimes the pale blue glow from an airplane engine would give it away and allow the German fighter to creep up behind it, undetected, and then unleash a hail of machine gun and cannon fire. Most of the time the bombers slipped through the fighter screen to hit their targets.

As the war progressed, so did the technology. German engineers managed to scale down radar sets, and create the first portable computers, so that night fighters could carry their own radar. They no longer needed to strain their sight into the dark skies. Bomber Command also increased its abilities with the introduction of the Avro Lancaster heavy bomber in 1942. These four-engined behemoths would become the iconic workhorses of Bomber Command. With a crew of 7 and carrying radar themselves, they were able to fly to Poland and back with a huge payload of 22,000 lbs of bombs.

The Americans concentrated on pinpoint bombing of factories during the day, resulting in massive casualties. This formation of American B-17s are headed for Schweinfurt, 1943.

Commonwealth bombers, including Canadians, firebombed entire cities at night. The mix of US raids during the day followed by Commonwealth raids at night was called “Round the Clock Bombing”

The Avro Lancaster was introduced in 1942, and would prove to be one of the best killing machines of the Second World War. Canadians were among the first squadrons to take delivery.

The night Bombing War would escalate into a frenzy of mass killing and destruction. By 1943 Canada’s bomber squadrons were organized into one powerful unit, 6 Group, part of the RAF Bomber Command. They were in action every single night. In the early afternoon a Mosquito high-altitude plane would take off to recon a target for weather and defense information. Then aircrews were summoned to a briefing where they were given their targets. Men were then allowed to sleep and eat in preparation for the upcoming night. Most weren’t hungry and fear and fatalism set in during these last hours.

Meanwhile, ground crews prepared the planes and loaded fuel and bombs while women WAAFs (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force) prepared the crew’s equipment, parachutes and the trucks that would take them to their dispersal aprons on the tarmac. WAAFs were also responsible for radio communications, administration (including payroll), map reading, intelligence analysis and radar control.

As the sun set the aircrews would be driven out to their awaiting airplanes, where they would have one last cigarette together and the tail gunner would urinate on the tail wheel for good luck (a tradition common with all air forces around the world). Then the heavily-laden men would climb aboard. Engines would be started and the heavy Lancasters would rumble to their takeoff positions. Each airfield held about 30 bombers, so one after another they planes would roll down the runway, heavily burdened with fuel and bombs, and would barely lift off the ground before thundering over a farm field or small English village.

All the aircraft from all the airfields in England would join up into a ‘stream’, each plane flying independently in the night sky but in the general direction as all the others. The skies over Europe would be filled with the thundering hum of 1,000 heavy bombers as the stream pressed on to its target somewhere in Germany.

German fighters, many with radar, would dart into the stream along its entire length. Brilliant flashes from exploding airplanes would fill the sky for a moment and then die as the burning plan dropped out of the sky into the clouds below. Tail gunners were the first point of contact for enemy fighters. Tail gunners were alone and isolated in their turrent, and spent long hours scanning the night sky with tired eyes. When they did spot a German fighter, it was usually sudden and too late. “Messerschmidt twelve o’clock!” they would scream into their radio, unleashing a burst of heavy machine gun fire from their quad-mounted turret. Then a blast of German cannon fire would decimate rear section of the airplane and smash the wings and engines. The fuel would light up and the plane would go into a burning spin as the crew desperately tried to bail out, held back by powerful G-forces.

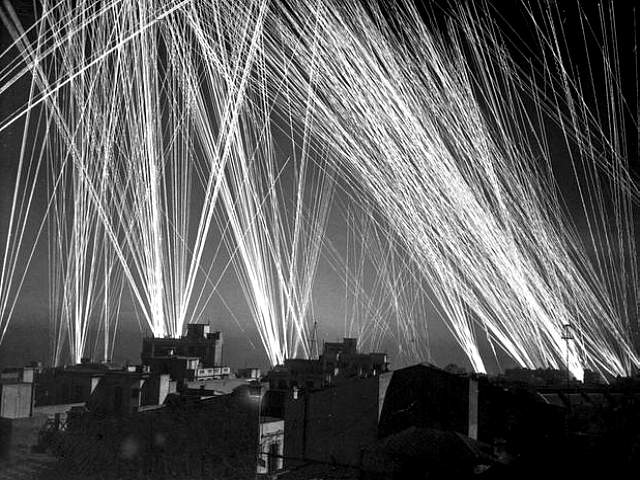

For those planes that made it over the target, an eerie site awaited them. Searchlights swept the skies around while bursts of exploding flak surrounded them. The pathfinders, advance aircraft tasked with marking the targets, were dropping their clouds of bright green and red flares over the center of a German city, guiding the rest of the stream in. Then the bombs began to fall. As each plane released its load it would leap into the air with the sudden loss of weight. The explosions on the doomed city below illuminated the entire scene. Suddenly a searchlight cone would snap onto a plane. Its only hope of survival was to dive out of it. The men’s noses and ears would bleed from the pressure of the dive. If the plane escaped it would turn back to England, where German fighters awaited the stream again.

Damaged planes and those with wounded on board received priority landing in England as the sun came up. Many aircraft, badly damaged by German fighters or flak, crashed in England. After every raid the hospitals were filled with burned and maimed men, carried home on limping Lancasters.

This continued night after night, growing in intensity as the sophistication of killing grew.

The scene over a burning German city at night was eerie, with the flares, bombs and flak exploding everywhere.

The tail gunner had the lowest survival rate of any aircrew during world war 2. 4,713 Canadian tail gunners died in the skies over Europe.

In 1943, under the name “Operation Ghemorra”, Bomber Command set its sights on the German city of Hamburg. Hamburg had been largely spared bombing, as it had very few military or industrial uses. Nevertheless, in July of 1943, over the course of a week. US and Commonwealth bombers leveled the city in one of the worst disasters in history.

No comments:

Post a Comment