League of Nations mandate

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administering the territory on behalf of the League. These were of the nature of both a treaty and a constitution, which contained minority rights clauses that provided for the rights of petition and adjudication by the International Court.[1] The mandate system was established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, entered into on 28 June 1919. With the dissolution of the League of Nations after World War II, it was stipulated at the Yalta Conference that the remaining Mandates should be placed under the trusteeship of the United Nations, subject to future discussions and formal agreements. Most of the remaining mandates of the League of Nations (with the exception of South-West Africa) thus eventually becameUnited Nations Trust Territories.

Contents

[hide]Generalities[edit]

All of the territories subject to League of Nations mandates were previously controlled by states defeated in World War I, principally Imperial Germany and the Ottoman Empire. The mandates were fundamentally different from the protectorates in that the Mandatory power undertook obligations to the inhabitants of the territory and to the League of Nations.

The process of establishing the mandates consisted of two phases:

- The formal removal of sovereignty of the state previously controlling the territory.

- The transfer of mandatory powers to individual states among the Allied Powers.

Treaties[edit]

The divestiture of Germany's overseas colonies, along with three territories disentangled from its European homeland area (the Free City of Danzig, Memel Territory, and Saar), was accomplished in the Treaty of Versailles (1919), with the territories being allotted among the Allies on May 7 of that year. Ottoman territorial claims were first addressed in theTreaty of Sèvres (1920) and finalized in the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). The Turkish territories were allotted among the Allied Powers at the San Remo conference in 1920.

Hidden agendas and objections[edit]

Peace treaties have played an important role in the formation of the modern law of nations.[2] Many rules that govern the relations between states have been introduced and codified in the terms of peace treaties.[3] The first twenty-six articles of the Versailles Treaty of 28 June 1919 contained the Covenant of the League of Nations. It contained the international machinery for the enforcement of the terms of the treaty. Article 22 established a system of Mandates to administer former colonies and territories.

Legitimacy of the allocations[edit]

Article 22 was written two months before the signing of the peace treaty, before it was known what communities, peoples, or territories were related to sub-paragraphs 4, 5, and 6. The treaty was signed, and the peace conference had been adjourned, before a formal decision was made.[citation needed] The mandates were arrangements guaranteed by, or arising out of the general treaty which stipulated that mandates were to be exercised on behalf of the League.

The treaty contained no provision for the mandates to be allocated on the basis of decisions taken by four members of the League acting in the name of the so-called "Principal Allied and Associated Powers". The decisions taken at the conferences of the Council of Four were not made on the basis of consultation or League unanimity as stipulated by the Covenant. As a result, the actions of the conferees were viewed by some as having no legitimacy.[4]

In testimony before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations a former US State Department official who had been a member of the American Commission at Paris, testified that the United Kingdom and France had simply gone ahead and arranged the world to suit themselves. He pointed out that the League of Nations could do nothing to alter their arrangements, since the League could only act by unanimous consent of its members - including the UK and France.[5]

United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing was a member of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace at Paris in 1919. He explained that the system of mandates was a device created by the Great Powers to conceal their division of the spoils of war under the color of international law. If the former German and Ottoman territories had been ceded to the victorious powers directly, their economic value would have been credited to offset the Allies' claims for war reparations.[6] Article 243 of the treaty instructed the Reparations Commission that non-mandate areas of the Saar and Alsace-Lorraine were to be reckoned as credits to Germany in respect of its reparation obligations.[7]

Legitimacy of the provisions[edit]

| This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Lack of sources, broken links, excessive focus on US concerns. (November 2012) |

Under the plan of the US Constitution the Congress was delegated the power to declare or define the Law of Nations in cases where its terms might be vague or indefinite. The US Senate refused to ratify the Covenant of the League of Nations.[citation needed] The legal issues surrounding the rule by force and the lack of self-determination under the system of mandates were cited by the Senators who withheld their consent.[8][9] The US government subsequently entered into individual treaties to secure legal rights for its citizens, to protect property rights and businesses interests in the mandates, and to preclude the mandatory administration from altering the terms of the mandates without prior US approval.[10]

The United States filed a formal protest because the preamble of the mandates indicated to the League that they had been approved by the Principal Allied and Associated Powers, when, in fact, that was not the case.[11]

The Official Journal of the League of Nations, dated June 1922, contained a statement by Lord Balfour (UK) in which he explained that the League's authority was strictly limited. The article related that the 'Mandates were not the creation of the League, and they could not in substance be altered by the League. The League's duties were confined to seeing that the specific and detailed terms of the mandates were in accordance with the decisions taken by the Allied and Associated Powers, and that in carrying out these mandates the Mandatory Powers should be under the supervision—not under the control—of the League.'[12]

Types of mandates[edit]

The League of Nations decided the exact level of control by the Mandatory power over each mandate on an individual basis. However, in every case the Mandatory power was forbidden to construct fortifications or raise an army within the territory of the mandate, and was required to present an annual report on the territory to the League of Nations.

The mandates were divided into three distinct groups based upon the level of development each population had achieved at that time.

Class A mandates[edit]

The first group, or Class A mandates, were territories formerly controlled by the Ottoman Empire that were deemed to "... have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognized subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone. The wishes of these communities must be a principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory."

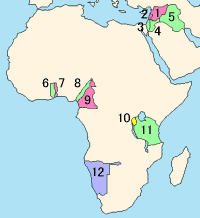

The Class A mandates were:

- Palestine (United Kingdom), from 29 September 1923 – 15 May 1948.[13][14][15] In April 1921, Transjordan provisionally became an autonomous area for 6 months but then continued to be part of the Mandate until independence.[16][17] It eventually became the independent HashemiteKingdom of Transjordan (later Jordan) on 25 May 1946. A plan for peacefully dividing the remainder of the Mandate failed. The Mandate terminated at midnight between 14 and 15 May 1948. On the evening of 14 May, the Chairman of the Jewish Agency for Palestine had declared the establishment of the State of Israel.[18] Following the war, 75% of the area west of the Jordan River was controlled by the new State ofIsrael.[19] Other parts, until 1967, formed the West Bank of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip.

- Syria (France), 29 September 1923 – 1 January 1944. This mandate included Lebanon; Hatay (a former Ottoman Alexandretta sandjak) broke away from it and became a French protectorate until it was ceded to the new Republic of Turkey. Following the termination of the French mandate, two separate independent republics, Syria and Lebanon, were formed.

- Mesopotamia (United Kingdom), not enacted and replaced by the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty

Class B mandates[edit]

The second group of mandates, or Class B mandates, were all former Schutzgebiete (German territories) in West and Central Africa which were deemed to require a greater level of control by the mandatory power: "...the Mandatory must be responsible for the administration of the territory under conditions which will guarantee freedom of conscience and religion." The mandatory power was forbidden to construct military or naval bases within the mandates.

The Class B mandates were:

- Ruanda-Urundi (Belgium), from 20 July 1922 to 13 December 1946. Formerly two separate German protectorates, they were joined as a single mandate on 20 July 1922. From 1 March 1926 to 30 June 1960, Ruanda-Urundi was in administrative union with the neighbouring colony of Belgian Congo. After 13 December 1946, it became a United Nations Trust Territory, remaining under Belgian administration until the separate nations of Rwanda and Burundi gained independence on 1 July 1962.

- Tanganyika (United Kingdom), from 20 July 1922 to 11 December 1946. It became a United Nations Trust Territory on 11 December 1946, and was granted internal self-rule on 1 May 1961. On 9 December 1961, it became an independent Commonwealth realm, transforming into a republic on the same day the next year. On 26 April 1964, Tanganyika merged with the neighbouring island of Zanzibar to become the modern nation of Tanzania.

- Kamerun was split on 20 July 1922 into British Cameroons (under a Resident) and French Cameroun (under a Commissioner until 27 August 1940, then under a Governor), on 13 December 1946 transformed into United Nations Trust Territories, again a British (successively under senior district officers officiating as Resident, a Special Resident and Commissioners) and a French Trust (under a Haut Commissaire)

- Togoland was split into British Togoland (under an Administrator, a post filled by the colonial Governor of the British Gold Coast (present Ghana) except 30 September 1920–11 October 1923 Francis Walter Fillon Jackson) and French Togoland (under a Commissioner) (United Kingdom and France), 20 July 1922 separate Mandates, transformed on 13 December 1946 into United Nations trust territories, French Togoland (under a Commissioner till 30 August 1956, then under a High Commissioner as Autonomous Republic of Togo) and British Togoland (as before; on 13 December 1956 it ceased to exist as it became part of Ghana)

Class C mandates[edit]

The Class C mandates, including South West Africa and certain of the South Pacific Islands, were considered to be "best administered under the laws of the Mandatory as integral portions of its territory"

The Class C mandates were former German possessions:

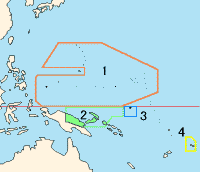

- former German New Guinea became the Territory of New Guinea (Australia/United Kingdom) from 17 December 1920 under a (at first Military) Administrator; after (wartime) Japanese/U.S. military commands from 8 December 1946 under UN mandate as North East New Guinea (under Australia, as administrative unit), until it became part of present Papua New Guinea at independence in 1975

- Nauru, formerly part of German New Guinea (Australia in effective control, formally together with United Kingdom and New Zealand) from 17 December 1920, 1 November 1947 made into a United Nations trust territory (same three powers) until its 31 January 1968 independence as a Republic - all that time under an Administrator

- former German Samoa (New Zealand/United Kingdom) 17 December 1920 a League of Nations mandate, renamed Western Samoa (as opposed to American Samoa), from 25 January 1947 a United Nations trust territory until its 1 January 1962 independence

- South Pacific Mandate (Japan)

- South West Africa (South Africa/United Kingdom)

- from 1 October 1922, Walvisbaai's administration (still merely having a Magistrate until its 16 March 1931 Municipal status, thence a Mayor) was also assigned to the mandate

Rules of establishment[edit]

According to the Council of the League of Nations, meeting of August 1920:[20] "draft mandates adopted by the Allied and Associated Powers would not be definitive until they had been considered and approved by the League ... the legal title held by the mandatory Power must be a double one: one conferred by the Principal Powers and the other conferred by the League of Nations,"[21]

Three steps were required to establish a Mandate under international law: (1) The Principal Allied and Associated Powers confer a mandate on one of their number or on a third power; (2) the principal powers officially notify the council of the League of Nations that a certain power has been appointed mandatory for such a certain defined territory; and (3) the council of the League of Nations takes official cognisance of the appointment of the mandatory power and informs the latter that it [the council] considers it as invested with the mandate, and at the same time notifies it of the terms of the mandate, after assertaining whether they are in conformance with the provisions of the covenant."[21][22]

The U.S. State Department Digest of International Law says that the terms of the Treaty of Lausanne provided for the application of the principles of state succession to the "A" Mandates. The Treaty of Versailles (1920) provisionally recognized the former Ottoman communities as independent nations.[23] It also required Germany to recognize the disposition of the former Ottoman territories and to recognize the new states laid down within their boundaries.[24] The terms of the Treaty of Lausanne required the newly created states that acquired the territory detached from the Ottoman Empire to pay annuities on the Ottoman public debt and to assume responsibility for the administration of concessions that had been granted by the Ottomans. The treaty also let the States acquire, without payment, all the property and possessions of the Ottoman Empire situated within their territory.[25] The treaty provided that the League of Nations was responsible for establishing an arbital court to resolve disputes that might arise and stipulated that its decisions were final.[25]

A disagreement regarding the legal status and the portion of the annuities to be paid by the "A" mandates was settled when an Arbitrator ruled that some of the mandates contained more than one State:

Later history[edit]

After the United Nations was founded in 1945 and the League of Nations was disbanded, all but one of the mandated territories that remained under the control of the mandatory power became United Nations trust territories, a roughly equivalent status. In each case, the colonial power that held the mandate on each territory became the administering power of the trusteeship, except that Japan, which had been defeated in World War II, lost its mandate over the South Pacific islands, which became a "strategic trust territory" known as the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands under United States administration.

The sole exception to the transformation of League of Nations mandates into UN trusteeships was that South Africa refused to place South-West Africa under trusteeship. Instead, South Africa proposed that it be allowed to annex South-West Africa, a proposal rejected by the United Nations General Assembly. The International Court of Justice held that South Africa continued to have international obligations under the mandate for South-West Africa. The territory finally attained independence in 1990 as Namibia, after a long guerrilla war of independence against the apartheid regime.

Nearly all the former League of Nations mandates had become sovereign states by 1990, including all of the former United Nations Trust Territories with the exception of a few successor entities of the gradually dismembered Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (formerly Japan's South Pacific Trust Mandate). These exceptions include the Northern Mariana Islands which is a commonwealth in political union with theUnited States with the status of unincorporated organized territory. The Northern Mariana Islands does elect its own governor to serve as territorial head of government, but it remains a U.S. territory with itshead of state being the President of the United States and federal funds to the Commonwealth administered by the Office of Insular Affairs of the United States Department of the Interior.

Remnant Micronesia and the Marshall Islands, the heirs of the last territories of the Trust, attained final independence on 22 December 1990. (The UN Security Council ratified termination of trusteeship, effectively dissolving trusteeship status, on 10 July 1987). The Republic of Palau, split off from the Federated States of Micronesia, became the last to get its independence effectively on 1 October 1994.

Sources and references[edit]

- Tamburini, Francesco "I mandati della Società delle Nazioni", in «Africana, Rivista di Studi Extraeuropei», n.XV - 2009, pp. 99–122.

- Anghie, Antony "Colonialism and the Birth of International Institutions: Sovereignty, Economy, and the Mandate System of the League of Nations" 34(3) New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 513 (2002)

- WorldStatesmen - links to each present nation

References[edit]

| Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (July 2014) |

- ^ "Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970)". International Court of Justice: 28–32. 21 June 1971. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ Peace Treaties and International Law in European History, From the Late Middle Ages to World War One

- ^ See 'The Law of Nations or the Principles of Natural Law', Emmerich de Vattel, 1758, Book IV: Of The Restoration of Peace: And of Embassies, Chapter 2: Treaties of Peace.

- ^ see for example The Century, The San Remo Conference, By Herbert Gibbons

- ^ Project Gutenberg: The Peace Negotiations by Robert Lansing, Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1921, Chapter XIX. 'THE BULLITT AFFAIR'

- ^ "Thus under the mandatory system Germany lost her territorial assets, which might have greatly reduced her financial debt to the Allies, while the latter obtained the German colonial possessions without the loss of any of their claims for indemnity. In actual operation the apparent altruism of the mandatory system worked in favor of the selfish and material interests of the Powers which accepted the mandates. And the same may be said of the dismemberment of Turkey.

...The truth of this was very apparent at Paris. In the tentative distribution of mandates among the Powers, which took place on the strong presumption that the mandatory system would be adopted, the principal European Powers appeared to be willing and even eager to become mandatories over territories possessing natural resources which could be profitably developed and showed an unwillingness to accept mandates for territories which, barren of mineral or agricultural wealth, would be continuing liabilities rather than assets. This is not stated by way of criticism, but only in explanation of what took place.Project Gutenberg: The Peace Negotiations by Robert Lansing, Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1921, Chapter XIII 'THE SYSTEM OF MANDATES' - ^ Peace Treaty of Versailles, Articles 231-247 and Annexes, Reparations

- ^ Senator Lodge, the Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, had attached a reservation which read: 'No mandate shall be accepted by the United States under Article 22, Part 1, or any other provision of the treaty of peace with Germany, except by action of the Congress of the United States.'Henry Cabot Lodge: Reservations with Regard to the Treaty and the League of Nations

- ^ Senator Borah, speaking on behalf on the 'Irreconcilables' stated 'My reservations have not been answered.' He completely rejected the proposed system of Mandates as an illegitimate rule by brute force. Classic Senate Speeches and the Denunciation of the Mandate System, starting on page 7, col. 1

- ^ see for example DELAY IN EXCHANGE OF RATIFICATIONS OF THE PALESTINE MANDATE CONVENTION PENDING ADJUSTMENT OF CASES INVOLVING THE CAPITULATORY RIGHTS OF AMERICANS, 1925

- ^ see the text of the American note to the Council of the League of Nations, dated February 1, 1921

- ^ Excerpts from League of Nations Official Journal dated June 1922, pp. 546-549

- ^ "Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919 Volume XIII, Annotations to the treaty of peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany, signed at Versailles, June 28, 1919:". Foreign Relations of the United States. United States State Department. June 28, 1919. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory". Advisory Opinions. The International Court of Justice (ICJ). 2004. p. 165. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

70. Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire. At the end of the First World War, a class "A" Mandate for Palestine was entrusted to Great Britain by the League of Nations, pursuant to paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the Covenant

- ^ "ITALY HOLDS UP CLASS A MANDATES". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. July 20, 1922. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

LONDON, July 19.--The A mandates, which govern the British occupation of Palestine and the French occupation of Syria, came today before the Council of the League of Nations.

- ^ The Making of Jordan: Tribes, Colonialism and the Modern State, By Yoav Alon, Published by I.B.Tauris, 2007, ISBN 1-84511-138-9, page 21

- ^ Determining Boundaries in a Conflicted World: The Role of Uti Possidetis, By Suzanne Lalonde, Published by McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, 2002, ISBN 0-7735-2424-X, page 89-100

- ^ Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs: THE DECLARATION OF THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE STATE OF ISRAEL May 14, 1948: Retrieved 28 January 2013

- ^ Edmund Jan Osmańczyk; Anthony Mango (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: G to M. Taylor & Francis. p. 1178. ISBN 978-0-415-93922-5. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ (p109–110)

- ^ a b Quincy Wright, Mandates under the League of Nations, Univ. of Chicago Press, 1930.

- ^ See also: Temperley, History of the Paris Peace Conference, Vol VI, p505–506; League of Nations, The Mandates System (official publication of 1945); Hill, Mandates, Dependencies and Trusteeship, p133ff.

- ^ See Article 22 of the Peace Treaty of Versailles

- ^ See Article 434 of the Peace Treaty of Versailles

- ^ a b Article 47, 60, and Protocol XII, Article 9 of the Treaty of Lausanne

- ^ See Marjorie M. Whiteman, Digest of International Law, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1963) pp 650-652, Questia, Web, 21 Apr. 2010

Further reading[edit]

- Anghie, Antony. "Colonialism and the Birth of International Institutions: Sovereignty, Economy, and the Mandate System of the League of Nations." NYUJ Int'l L. & Pol. 34 (2001): 513.

- Bruce, Scot David, Woodrow Wilson's Colonial Emissary: Edward M. House and the Origins of the Mandate System, 1917-1919 (University of Nebraska Press, 2013).

- Callahan, Michael D. Mandates and empire: the League of Nations and Africa, 1914-1931 (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 1999)

- Haas, Ernst B. "The reconciliation of conflicting colonial policy aims: acceptance of the League of Nations mandate system," International Organization (1952) 6#4 pp: 521-536.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment