Palestinian Refugees,

Invited to leave in 1948

The people are in great need of a "myth" to fill their

consciousness and imagination....

-- Musa Alami, 1948Since 1948 Arab leaders have approached the Palestine problem

in an irresponsible manner.... they have used the Palestine

people for selfish political purposes. This is ridiculous and,

I could say, even criminal.

-- King Hussein of Jordan, 1960

Since 1948 it is we who demanded the return of the refugees... while it is we who made them leave.... We brought disaster upon ... Arab refugees, by inviting them and bringing pressure to bear upon them to leave.... We have rendered them dispossessed.... We have accustomed them to begging.... We have participated in lowering their moral and social level.... Then we exploited them in executing crimes of murder, arson, and throwing bombs upon ... men, women and children-all this in the service of political purposes .... [36]

-- Khaled Al-Azm, Syria's Prime Minister after the 1948 war

The nations of western Europe condemned Israel's position

despite their guarantee of her security.... They understood

that ... their dependence upon sources of energy precluded

their allowing themselves to incur Arab wrath.

-- Al-Haytham Al-Ayubi, Arab Palestinian military strategist, 1974

consciousness and imagination....

-- Musa Alami, 1948Since 1948 Arab leaders have approached the Palestine problem

in an irresponsible manner.... they have used the Palestine

people for selfish political purposes. This is ridiculous and,

I could say, even criminal.

-- King Hussein of Jordan, 1960

Since 1948 it is we who demanded the return of the refugees... while it is we who made them leave.... We brought disaster upon ... Arab refugees, by inviting them and bringing pressure to bear upon them to leave.... We have rendered them dispossessed.... We have accustomed them to begging.... We have participated in lowering their moral and social level.... Then we exploited them in executing crimes of murder, arson, and throwing bombs upon ... men, women and children-all this in the service of political purposes .... [36]

-- Khaled Al-Azm, Syria's Prime Minister after the 1948 war

The nations of western Europe condemned Israel's position

despite their guarantee of her security.... They understood

that ... their dependence upon sources of energy precluded

their allowing themselves to incur Arab wrath.

-- Al-Haytham Al-Ayubi, Arab Palestinian military strategist, 1974

At the time of the 1948 war, Arabs in Israel were invited by their fellow Arabs -- invited to "leave" while the "invading" Arab armies would purge the land of Jews.1 The invading Arab governments were certain of a quick victory; leaders warned the Arabs in Israel to run for their lives.2

In response, the Jewish Haifa Workers' Council issued an appeal to the Arab residents of Haifa: [See Official British Police Report ]

For years we have lived together in our city, Haifa.... Do not fear: Do not destroy your homes with your own hands ... do not bring upon yourself tragedy by unnecessary evacuation and self-imposed burdens.... But in this city, yours and ours, Haifa, the gates are open for work, for life, and for peace for you and your families."3While the Haifa pattern appears to have been prevalent, there were exceptions. Arabs in another crucial strategic area, who were "opening fire on the Israelis shortly after surrendering,"4were "forced" to leave by the defending Jewish army to prevent what former Israeli Premier Itzhak Rabin described as a "hostile and armed populace" from remaining "in our rear, where it could endanger the supply route . . ."5 In his memoirs, Rabin stated that Arab control of the road between the seacoast and Jerusalem had "all but isolated" the "more than ninety thousand Jews in Jerusalem," nearly one-sixth of the new nation's total population.

If Jerusalem fell, the psychological blow to the nascent Jewish state would be more damaging than any inflicted by a score of armed brigades.6According to a research report by the Arab-sponsored Institute for Palestine Studies in Beirut, however, "the majority" of the Arab refugees in 1948 were not expelled, and "68%" left without seeing an Israeli soldier.7

After the Arabs' defeat in the 1948 war, their positions became confused: some Arab leaders demanded the "return" of the "expelled" refugees to their former homes despite the evidence that Arab leaders had called upon Arabs to flee. [Such as President Truman's International Development Advisory Board Report, March 7, 1951: "Arab leaders summoned Arabs of Palestine to mass evacuation... as the documented facts reveal..."] At the same time, Emile Ghoury, Secretary of the Arab Higher Command, called for the prevention of the refugees from "return." He stated in the Beirut Telegraph on August 6, 1948: "it is inconceivable that the refugees should be sent back to their homes while they are occupied by the Jews.... It would serve as a first step toward Arab recognition of the state of Israel and Partition."

Arab activist Musa Alami despaired: as he saw the problem, "how can people struggle for their nation, when most of them do not know the meaning of the word? ... The people are in great need of a 'myth' to fill their consciousness and imagination. . . ." According to Alami, ar indoctrination of the "myth" of nationality would create "identity" and "self-respect."8

However, Alami's proposal was confounded by the realities: between 1948 and 1967, the Arab state of Jordan claimed annexation of the territory west of the Jordan River, the "West Bank" area of Palestine -- the same area that would later be forwarded by Arab "moderates" as a "mini-state" for the "Palestinians." Thus, that area was, between 1948 and 1967, called "Arab land," the peoples were Arabs, and yet the "myth" that Musa Alami prescribed-the cause of "Palestine" for the "Palestinians" -- remained unheralded, unadopted by the Arabs during two decades. According to Lord Caradon, "Every Arab assumed the Palestinians [refugees] would go back to Jordan."9

When "Palestine" was referred to by the Arabs, it was viewed in the context of the intrusion of a "Jewish state amidst what the Arabs considered their own exclusive environment or milieu, the 'Arab region.' "10 As the late Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser "screamed" in 1956, "the imperialists' 'destruction of Palestine' " was "an attack on Arabnationalism," which " 'unites us from the Atlantic to the Gulf.' "11

Ever since the 1967 Israeli victory, however, when the Arabs determined that they couldn't obliterate Israel militarily, they have skillfully waged economic, diplomatic, and propaganda war against Israel. This, Arabs reasoned, would take longer than military victory, but ultimately the result would be the same. Critical to the new tactic, however, was a device designed to whittle away at the sympathies of Israel's allies: what the Arabs envisioned was something that could achieve Israel's shrinking to indefensible size at the same time that she became insolvent.

This program was reviewed in 1971 by Mohamed Heikal,12then still an important spokesman of Egypt's leadership in his post as editor of the influential, semi-official newspaper Al Ahram. Heikal called for a change of Arab rhetoric -- no more threats of "throwing Israel into the sea" -- and a new political strategy aimed at reducing Israel to indefensible borders and pushing her into diplomatic and economic isolation. He predicted that "total withdrawal" would "pass sentence on the entire state of Israel."

As a more effective means of swaying world opinion, the Arabs adopted humanitarian terminology in support of the "demands" of the "Palestinian refugees," to replace former Arab proclamations of carnage and obliteration. In Egypt, for example, in 1968 "the popularity of the Palestinians was rising," as a result of Israel's 1967 defeat of the Arabs and subsequent 1968 "Israeli air attacks inside Egypt."13] It was as recently as 1970 that Egyptian President Nasser defined "Israel" as the cause of "the expulsion of the Palestinian people from their land." Although Nasser thus gave perfunctory recognition to the "Palestinian Arab" allegation, he was in reality preoccupied with the overall basic, pivotal Arab concern. As he continued candidly in the same sentence, Israel was "a permanent threat to the Arab nation."14 Later that year (May 1970), Nasser "formulated his rejection of a Jewish state in Palestine," but once again he stressed the "occupation of our [Pan-Arab] lands," while only secondarily noting: "And we reject its [Israel's] insistence on denying the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people in their country."15Subsequently the Arabs have increased their recounting of the difficulties and travail of Arab refugees in the "host" countries adjacent to Israel. Photographs and accounts of life in refugee camps, as well as demands for the "legitimate" but unlimited and undefined "rights" of the "Palestinians," have flooded the communications media of the world in a subtle and adroit utilization of the art of professional public relations.16

A prominent Arab Palestinian strategist, AI-Haytham Al-Ayubi, analyzed the efficacy of Arab propaganda tactics in 1974, when he wrote:

The image of Israel as a weak nation surrounded by enemies seeking its annihilation evaporated [after 1967], to be replaced by the image of an aggressive nation challenging world opinion.* 17[* As Rosemary Sayigh wrote in the Journal of Palestine Studies, "a strongly defined Palestinian identity did not emerge until 1968, two decades after expulsion." It had taken twenty years to establish the "myth" prescribed by Musa Alami.18]

The high visibility of the sad plight of the homeless refugees -- always tragic -- has uniquely attracted the world's compassion.19 In addition, the campaign has provided non-Arabs with moral rationalization for abiding by the Arabs' anti-Israel rules, which are regarded as prerequisites to getting Arab oil and the financial benefits from Arab oil wealth. Millions of dollars have been spent to exploit the Arab refugees and their repatriation as "the heart of the matter," as the primary human problem that must be resolved before any talk of overall peace with Israel.

Reflecting on the oil weapon's influence in the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Al-Ayubi shrewdly observed:

The nations of western Europe condemned Israel's position despite their guarantee of her security and territorial integrity. They understood that European interests and their dependence upon sources of energy precluded their allowing themselves to incur Arab wrath.20Thus Al-Ayubi recommended sham "peace-talks," with the continuation, however, of the "state of 'no peace,'" and he advocated the maintaining of "moral pressure together with carefully-balanced military tension..." for the "success of thenew Arab strategy." Because "loss of human life remains a sore point for the enemy," continual "guerrilla" activities can erode Israel's self-confidence and "the faith" of the world in the "Israeli policeman."

Al-Ayubi cited, as an example, "the success of Arab foreign policy maneuvers" in 1973, which was

so total that.... With the exception of the United States and the racist African governments, the entire world took either a neutral or pro-Arab position on the question of legality of restoring the occupied territories through any means -- including the use of military force.As Al-Ayubi noted, "The basic Arab premise concerning 'the elimination of the results of aggression' remains accepted by the world." Thus the "noose" will be placed around the neck of the "Zionist entity."

But the Arabs' creation of the "myth" of nationality did not create the advantageous situation for the Palestinian Arabs that Musa Alami had hoped for. Instead, the conditions he complained of bitterly were perpetuated: the Arabs "shut the door" of citizenship "in their faces and imprison them in camps."21

Khaled Al-Azm, who was Syria's Prime Minister after the 1948 war, deplored the Arab tactics and the subsequent exploitation of the refugees, in his 1972 memoirs:

Since 1948 it is we who demanded the return of the refugees ... while it is we who made them leave.... We brought disaster upon ... Arab refugees, by inviting them and bringing pressure to bear upon them to leave.... We have rendered them dispossessed.... We have accustomed them to begging.... We have participated in lowering their moral and social level.... Then we exploited them in executing crimes of murder, arson, and throwing bombs upon ... men, women and children-all this in the service of political purposes .... 22Propaganda has successfully veered attention away from the Arab world's manipulation of its peoples among the refugee group on the one hand, and the number of those who now in fact possess Arab citizenship in many lands, on the other hand. The one notable exception is Jordan, where the majority of Arab refugees moved,* and where they are entitled to citizenship according to law, "unless they are Jews."23

Palestinian leadership will not let the refugee problem be solved In 1958, former director of UNRWA Ralph Galloway declared angrily while in Jordan that

The Arab states do not want to solve the refugee problem. They want to keep it as an open sore, as an affront to the United Nations, and as a weapon against Israel. Arab leaders do not give a damn whether Arab refugees live or die.Prittie, "Middle East Refugees," in Michael Curtis et al., eds., The Palestinians:

People, History, Politics (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books, 1975), p. 71.

---

1. Habib Issa, ed., Al-Hoda, Arabic daily, June 8, 1951, New York; see Economist (London), May 15, 1948, regarding "panic flight"; also see Economist, October 2, 1948, for British eyewitness report of Arab Higher Committee radio "announcements" that were "urging all Arabs in Haifa to quit."

2. Near East Arabic Radio, April 3, 1948: "It must not be forgotten that the Arab Higher Committee encouraged the refugees to flee from their homes in Jaffa, Haifa and Jerusalem, and that certain leaders . . . make political capital out of their miserable situation . . ." Cited by Anderson et al., "The Arab Refugee Problem and How It Can Be Solved," p. 22; for more regarding Arab responsibility, see Sir Alexander Cadogan, Ambassador of Great Britain to the United Nations, speech to the Security Council, S.C., O.R., 287th meeting, April 23, 1948; also see Harry Stebbens, British Port Officer stationed in Haifa, letter in Evening Standard (London), January 10, 1969.

3. April 28, 1948; according to the Economist (London), October 1, 1948, only "4000 to 6000" of the "62,000 Arabs who formerly lived in Haifa" remained there until the time of the war; also see Kenneth Bilby, New Star in the Near East (New York: Doubleday, 1950), pp. 30-31; Lt. Col. Moshe Pearlman, The Army of Israel (New York: Philosophical Library, 1950), pp. 116-17; and Major E. O'Ballance, The Arab-Israeli War of 1948 (London, 1956), p. 52.

4. David Shipler, New York Times, October 23, 1979, p. A3. Shipler cites Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, 0 Jerusalem, and Dan Kurzman, Genesis 1948.

5. New York Times, October 23, 1979.

6. Yitzhak Rabin, The Rabin Memoirs (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown, 1979), p. 23, pp. 22-44.

7. Peter Dodd and Halim Barakat, River Without Bridges.- A Study of the Exodus of the 1967Arab Palestinian Refugees (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1969), p. 43; on April 27, 1950, the Arab National Committee of Haifa stated in a memorandum to the Arab States: "The removal of the Arab inhabitants ... was voluntary and was carried out at our request ... The Arab delegation proudly asked for the evacuation of the Arabs and their removal to the neighboring Arab countries.... We are very glad to state that the Arabs guarded their honour and traditions with pride and greatness." Cited by J.B. Schechtman, The Arab Refugee Problem (New York: Philosophical Library, 1952), pp. 8-9; also see Al-Zaman, Baghdad journal, April 27, 1950.

8. Musa Alami, "The Lesson of Palestine," The Middle East Journal, October 1949.

9. Lord Caradon, "Cyprus and Palestine," lecture at the University of Chicago, Center for Middle Eastern Studies, February 17, 1976. Similar statement by Folke Bernadotte, To Jerusalem, p. 113.

10. P.J. Vatikiotis, Nasser and His Generation (London: Croom Heim, 1978), pp. 256-57.

11. Ibid. p. 234, quoting a speech by Nasser at Suez, July 26, 1956; in 1952, Sheikh Pierre Gemayel, then leader of the Lebanese National Youth Organization "Al Kataeb," wrote: "Why should the refugees stay in Lebanon, and not in Egypt, Iraq and Jordan which claim that they are all Arab and beyond that, Moslem? ... Isn't it for that alone that these so-called nationalist elements are demanding to resettle the refugees in Lebanon because they are themselves Arab and Moslems?" Al-Hoda, Lebanese journal, January 3, 1952, cited in Schechtman, Arab Refugee Problem, p. 84; also see Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, "Quest for an Arab Future," in Arab Journal, 1966-67, vol. 4, nos. 2-4, pp. 23-29.

12. "Mohammed Hassanein Heykal Discusses War and Peace in the Middle East," Journal of Palestine Studies, Autumn 197 1. Heykal thus joined the Arab chorus heard after the 1967 war.

13. Vatikiotis, Nasser, p. 257; also see Mohamed Heikal, The Road to Ramadan (New York: Ballantine Books, 1975), p. 56.

14. Interview with Nasser, Le Monde (Paris: February 1970), cited in Vatikiotis, Nasser, p. 259.

15. Charles Foltz, interview with Nasser, U.S. News and World Report, May 1970, cited in Vatikiotis, Nasser, p. 259; see also Le Monde interview, February 1970.

16. contrary to the popular view ... in the West," a "great many refugees" were living out of camps "in comfortable housing outside," in the beginning of the 1960s according to Fawaz Turki, The Disinherited- Journal of a Palestinian Exile (New York and London: Monthly Review Press, 1972), p. 41.

17. Al-Haytham A]-Ayubi, "Future Arab Strategy in the Light of the Fourth War," Shuun Filastiniyya (Beirut), October 1974. AI-Ayubi, also called Abu-Hammam, has been military head of Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, Lieutenant Colonel in the Syrian army, and highly respected strategist on Israel. He perceived the "guerrilla" war against Israel as the ultimately successful one.

18. Rosemary Sayigh, "Sources of Palestinian Nationalism: A Study of a Palestinian Camp in Lebanon," Journal of Palestinian Studies, vol. 6, no. 4, 1977, p. 2 1; see also Sayigh, "The Palestinian Identity Among Camp Residents," Journal of Palestinian Studia vol. 6, no. 3, 1977, pp. 3-22.

19. In 1981, the Organization of African Unity's executive secretary, Ambassador Oumarou Garba Youssoupou from Niger, reflected upon why the millions of displaced souls in Africa were not as visible: "We're not getting the publicity because of our culture. No refugee is turned away from the host countries, so we're not dramatic enough for television. We have no drownings, no piratings.... We don't make the news ... .. Aiding Africa's Refugees," by Gertrude Samuels, The New Leader, May 4, 1981.

20. AI-Ayubi, "Future Arab Strategy in the Light of the Fourth War."

21. Musa Alami, "The Lesson of Palestine," The Middle East Journal, October 1949.

22. Khaled Al-Azm, Memoirs [Arabic), 3 vols. (AI-Dar al Muttahida Id-Nashr, 1972), vol. 1, pp. 386-87, cited by Maurice Roumani, The Case of the Jewsfrom Arab Countries: A Neglected Issue, preliminary edition (Jerusalem: World Organization of Jews from Arab Countries [WOJAC], 1975), p. 61.

23. Jordanian National Law, Official Gazette, No. 1171, February 16, 1954, p. 105, Article 3(3). Between 1948 and 1967, 200,000 to 300,000 Arabs moved from the West Bank to the "East Bank," according to Eliyahu Kanovsky, in Jordan, People and Politics in the Middle East, Michael Curtis, ed. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books, 1971), p. 111.

How many Palestinians Refugees?

Inflating the numbers

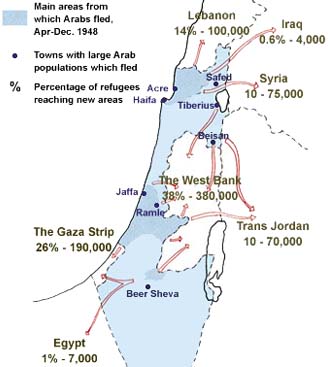

Arabs, encouraged by their leaders to leave, fled from what is now Israel between April and December, 1948.1 The Arab leaders promised them that they would soon be able to return following Israel's destruction. In some cases the Jews, including Israel's first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, urged the Arabs to remain, promising that they would not be harmed.2 Those who remained became full and equal citizens of Israel, while those who chose to leave went to neighboring Arab states. Instead of welcoming their Arab brothers, and integrating them into the mainstream of their societies, the Arab states kept them in squalid refugee camps and used these Palestinians refugees as political pawns in their fight against Israel.

Arabs, encouraged by their leaders to leave, fled from what is now Israel between April and December, 1948.1 The Arab leaders promised them that they would soon be able to return following Israel's destruction. In some cases the Jews, including Israel's first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, urged the Arabs to remain, promising that they would not be harmed.2 Those who remained became full and equal citizens of Israel, while those who chose to leave went to neighboring Arab states. Instead of welcoming their Arab brothers, and integrating them into the mainstream of their societies, the Arab states kept them in squalid refugee camps and used these Palestinians refugees as political pawns in their fight against Israel. 1. Irving Howe and Carl Gershman (eds.), Israel, the Arabs and the Middle East (New York: Bantam, 1972), p. 168.

2. See, for instance, The Economist, Oct. 2, 1948, for a description of Jewish efforts in Haifa to persuade the Arabs to stay.

Source: The Jewish Agency for Israel: The Arab Refugees 1948

According to various estimates, the accurate number of Arab refugees who left Israel in 1948 was somewhere between 430,000 and 650,000. * An oft-cited study that used official records of the League of Nations' mandate and Arab census figures[37] determined that there were 539,000 ** Arab refugees in May 1948.[38]

* The Statistical Abstract of Palestine in 1944-45 set the figure for the total Arab population living in the Jewish-settled territories of Palestine at 570,800.

** Walter Pinner began with a total of 696,000 Arabs living within the Armistice lines in 1948, from which he subtracted the 140,000-157,000 who remained in their homes when Israel became independent. Pinner further asserts that no more than 430,000 were "genuine refugees" in need of relief. See the population study in Chapter 12 of "From Time Immemorial" for new information and a detailed breakdown.

There was heated controversy over the exact number of Arab refugees who left Israel. In October 1948, there were already three "official" sets of figures: The United Nations had two, the higher of which estimated the number would "shortly increase to 500,000";[40] the Arab League's official figures reported a total already greater by almost 150,000 than the higher of the UN figures. The swollen Arab League figures could never be verified because the Arabs refused to allow official censuses to be completed among the refugees." Observers have deduced that the Arab purpose was to seek greater world attention through an exaggerated population figure and thereby induce the UN to put heavier pressures upon Israel, to force "repatriation."

But the propaganda use of erroneous, inflated, or otherwise manipulated population statistics was not a recent phenomenon restricted to the Arab refugee camps. As subsequent chapters reveal, this practice has long played a critical, underestimated role in shaping the perceptions and the resolution---or the lack of resolution---of the Arab-Israeli conflict.[39]

The former Director of Field Operations for the United Nations Disaster

Relief Project reported in July 1949 that

It is believed that some local [Arab] welfare cases are included in the refugee figures.[42]When the United Nations Relief and Work Agency (UNRWA) was established as a singular, special unit to deal with Arab refugees, practically its first undertaking, in May 1950, was an attempted refugee census to separate the genuinely desperate from the "fradulent claimants." After a year's time and a $300,000 expenditure, UNRWA reported that "it is still not possible to give an absolute figure of the true number of refugees as understood by the working definition of the word" [43] For the purpose of that census, the definition of "refugee" was "a person normally resident in Palestine who had lost his home and his livelihood as a result of the hostilities and who is in need." A reason given by UNRWA for falsified numbers was that the refugees "eagerly report births and ... reluctantly report deaths."[44]

One of the first official reports to question the accuracy of the refugee figures stated that there could be "no true refugee population" figures because the agency director "did not consider it practicable to ask the operating agencies to impose any kind of eligibility test and ... had no observers of his own for this purpose.'"[45] The report stated it was having difficulty excluding "ordinarily nomadic Bedouins and ... unemployed or indigent local residents" from genuine refugees, and

it cannot be doubted that in many cases individuals who could not qualify as being bona fide refugees are in fact on the relief rolls.One of the camp workers in Lebanon who was questioned about the accuracy of the refugee count answered,

We try to count them, but they are coming and going all the time; or we count them in Western clothes, then they return in aba and kafflyah and we count the same ones again.[46]UNRWA's relief rolls from the beginning were inflated by more than a hundred thousand,* including those who could not qualify as refugees from Israel even under the newer, unprecedentedly broad eligibility criterion for the refugee relief rolls. UNRWA now altered its definition of "refugees" to include those people who had lived in "Palestine" a minimum of only two years preceding the 1948 conflict." In addition, the evidence of fraud in the count, which accumulated over the years, was given no cognizance toward reducing the UN estimates. They continued to surge.

* UNRWA Director Howard Kennedy on November 1, 1950, reported to the United Nation Ad Hoc Political Committee that "a large group of indigent people totalling over 100,000 ... not be called refugees, but ... have lost their means of livelihood because of the war and post-war conditions ... The Agency felt their need was even more acute than that of the refugees who were fed and housed." In November 1950, Kennedy referred to "the 600,000 [Arab] refugees," although he had reported in May 1950 that UNRWA had distributed 860,000 rations, citing the hundreds of thousands of "hungry Arabs" who were not bona fide refugees but who claimed need.[47]

According to the Lebanese journal Al-Hayat, in 1959 "Of the 120,000 refugees who entered Lebanon, not more than 15,000 are still in camps."[49] A substantial de facto resettlement of Arab Palestinian refugees had actually taken place in Lebanon by 1959. Later that year AI-Hayat wrote that "the refugees' inclination-in spite of the noisy chorus all about them-is toward immediate integration."[50] The 1951-1952 UNRWA report itself had determined that "two-thirds of the refugees live elsewhere than in camps," and that "more fortunate refugees are not even on rations, but live rather comfortably ... and work at good jobs."[51] The recognition in the United Nations and in Arab journals that the refugee camps had largely been emptied, through absorption and resettlement ' raised appropriate subjects for inquiry with regard to correcting the number of persons receiving rations and seeking "repatriation."

After their 1960 investigation, Senators Gale McGee and Albert Gore[52] reported the surfeit of

Ration cards [which] have become chattel for sale, for rent or bargain by any Jordanian, whether refugee or not, needy or wealthy. These cards are used... almost as negotiable instruments.... many have acquired large numbers of ration cards ... rented or bartered to others who unjustifiably receive ... rations, much of which are now in the black market.At the same time, the UNRWA Director admitted that the Jordan ration lists alone "are believed to include 150,000 ineligibles and many persons who have died."[53] Officials told the two senators of twenty percent to thirty percent inflation of the relief rolls,[54] and an American representative on the UNRWA Advisory Board added, "I have actually seen merchants openly weighing and buying supplies from recipients of distribution centers."*[55]

* According to the Mideast Mirror, a weekly news review published by Arab News Agency of Cairo: "There are refugees who hold as many as 500 ration cards, 499 of them belonging to refugees long dead.... There are dealers in UNRWA food and clothing and ration cards to the highest bidder.... 'Refugee capitaliste is what UNRWA calls them." July 23, 1955.

In 1961, UNRWA Agency Director John Davis acknowledged that the United Nations refugee counts included "other victims of the conflict of 1948 " and that it would be wrong to deny them aid merely because they weren't legaliy qualified.[56] However, they were persons neglected by their own Arab govern- ments, and they should not have been counted among the Arab refugees from Israel; by continuing to be unfaithful to its own mandate, UNRWA contributed to further distortion of an already misrepresented and misunderstood refugee situation. In fact, what were originally intended as humanitarian endeavors to aid needy Arab resident populations by the Red Cross and others would unwittingly contribute to the use of hapless humans for an entire political and military campaign. [57]

37. Jordanian National Law, Official Gazette, No. 1171, February 16, 1954, p. 105, Article 3(3). Between 1948 and 1967, 200,000 to 300,000 Arabs moved from the West Bank to the "East Bank," according to Eliyahu Kanovsky, in Jordan, People and Politics in the Middle East, Michael Curtis, ed. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books, 1971), p. 111.

38. In 1967, an additional 250,000 Arab refugees from the Israel-occupied territories were reported; added to the number who left in 1948, they brought the total to 789,000 Arab refugees.

39.A more current example of the traditional swelling of numbers was described by New York Times correspondent David Shipler during the 1982 Israeli routing of the PLO foundation in Lebanon. On July 14, Shipler wrote, "It is clear to anyone who has traveled in southern Lebanon ... that the original figures ... reported by correspondents quoting Beirut representatives of the Red Cross during the first week of the war, were extreme exaggerations."

40. This estimate was made by officers of the Disaster Relief Organization and confirmed by statistical calculation of the potential number of refugees who might have left after the second truce. Gabbay, Political Study, p. 166.

41. Marguerite Cartwright, "Plain Speech on the Arab Refugee Problem," in Land Reborn, American Christian Palestine Committee, November-December 1958; according to a United Nations Interim Report, 1951, A/145/Rev. 1, p. 17: ". . . the figures for Lebanon (128,000) are confused, due to the fact that many Lebanese nationals ... claimed status as refugees"; UNRWA was "forbidden" by Jordan Syria, and Gaza from counting newborn children among refugees, according to Falastin, Jordanian daily, January 25, 1956; see Joseph Schectman, The Refugee in the World (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1963), pp. 201-207.

42. W. de St. Aubin, Director of Field Operations for the UN Disaster Relief Project, "Peace and Refugees in the Middle East," The Middle East Journal, vol. iii, no. 3. July 1949.

43. Report of the Director, Special Report of Director and Advisory Commission, UNRWA to Sixth Session, General Assembly, UN Document A/1905; compare, for example, with OAU (Organization of African Unity) definition at 1969 Convention: "Any person compelled to leave his place of habitual residence Quoted in "Africa and Refugees," by Neville Rubin, African Affairs, July 1974, Journal of Royal African Society, University of London.

44. UNRWA, Annual Report of the Director, July 1, 1951, to June 30, 1952, General Assembly, Seventh Session, Supp. No. 13 W217 1). See also October 1950, UNRWA Interim Report of Director, A/ 145 1: "there is reason to believe that births are always registered for ration purposes, but deaths are often, if not usually, concealed so that the family may continue to collect rations for the deceased." Cited by Schechtman, Refugee in the World, p. 206.

45. Assistance to Palestine Refugees, Report on UN Relief to Palestine Refugees (UNPRP) from December 1948 to September 1949; the UNRWA staff was largely "Palestinian" and "nationals of the countries" concerned, "increasingly assuming larger duties" regarding "UNRWA's responsibility." UNRWA, Annual Report of the Director, July 195 I-June, 1952, G.A. 7th Session, Supp. No. 13 (A/217 1), p. 8. 46.Cartwright, "Plain Speech," cited by Schechtman, Refugee in the World, pp. 200-201.

47. UN General Assembly, Official Record, 5th session, Ad Hoc Political Committee 31st Meeting, November 11, 1950, p. 194, and Anderson et al, "Arab Refugee Problem and How It Can Be Solved," p. 26.

48. Special Report of the Director, UNRWA, 1954-55, UN Document A/2717.

49. Schechtman, Refugee in the World, p. 248, citing Al-Hayat (Lebanon), June 25,1959.

50. ibid., p. 249, citing AI-Hayat, August 14, 1959.

51. UNRWA, Annual Report of the Director, July 195 I-June 1952, General Assembly, 7th Session, Supp, No. 13 (A/2171), pp. 3, 10.

52.Cable by McGee and Gore from Amman, Jordan, to President Eisenhower, Secretary of State Christian Herter, and the United Nations, October 1959, while traveling in the Mideast for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and Senate Appropriations Committee.

53.Dr. John H. Davis, October 1959, cited in Schechtman, Refugee in the World, pp. 207-208.

54. Ibid., quoting George B. Vinson, UNRWA eligibility officer stationed in Jerusalem.

55. Dr. Harry Howard, from the United States Congressional Record, April 20, 1960.

56.UNRWA, Annual Report of the Director. Under the auspices of the Arab Information Center in New York, by 1970 Davis was reporting the figures he himself had proved erroneous and grossly inflated, as the bona fide refugee count. "Why Are There Still Arab Refugees?", The Arab World, Arab Information Center, New York, December 1969-January 1970, p. 3.

57.See New York Times, May 15, 1949; Life magazine, September 29, 1958; Time

magazine, December 2, 1957.

No comments:

Post a Comment